For years, Chicago leaders turned the city’s water supply into a revenue stream. Now, tens of thousands can’t keep up with the rising costs.

A billing error turned Sylvia Taylor’s life upside-down.

The bureaucratic nightmare started when Taylor inherited her family’s Englewood house. Taylor turned off the water in 2007 to prevent the pipes from bursting during the winter.

She didn’t think about the water again until the city sent her a notice more than a year later, alerting her that the water would be shut off. Attached was a bill for $1,100.

Taylor was shocked.

Taylor said that she spoke with the city’s water and finance departments in hopes that they would clear the error. Years of fighting with the city went by.

And the city continued to charge Taylor for water she wasn’t using — and fined her for a debt she didn’t really owe.

The city couldn’t provide an accounting of the water usage at the vacant, unmetered property since residents at such properties are charged not for the actual amount of water used but for an estimated amount of water usage based on a property’s size and the number of its plumbing fixtures.

In 2015, Taylor requested the water department send an inspector to verify that the building was vacant. A water department employee wrote in the report “entire building vacant, water shutoff since 2007.” However, the report went unnoticed for years.

Nearly 13 years after she turned off the water to her family home, the debt had ballooned to $25,253.

The city had filed a statutory lien against the property — a debt collection tactic that the city has used against people with long-standing water debt.

“If you’re calling them and you’re telling them you don’t have any water . . . but they charge you all these fees, it’s really upsetting,” Taylor said. “I thought I was being robbed, really robbed by the water department.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23005613/WATERDEBT_03.jpg) Manuel Martinez/WBEZ

Manuel Martinez/WBEZ

Taylor’s case showcases a number of problems with Chicago’s water debt — from the massive amounts owed by tens of thousands of residents who’ve failed to keep up with the rising cost of water over the past decade to the city’s troubled billing system, punitive fees and aggressive collection tactics.

A monthslong WBEZ investigation revealed that:

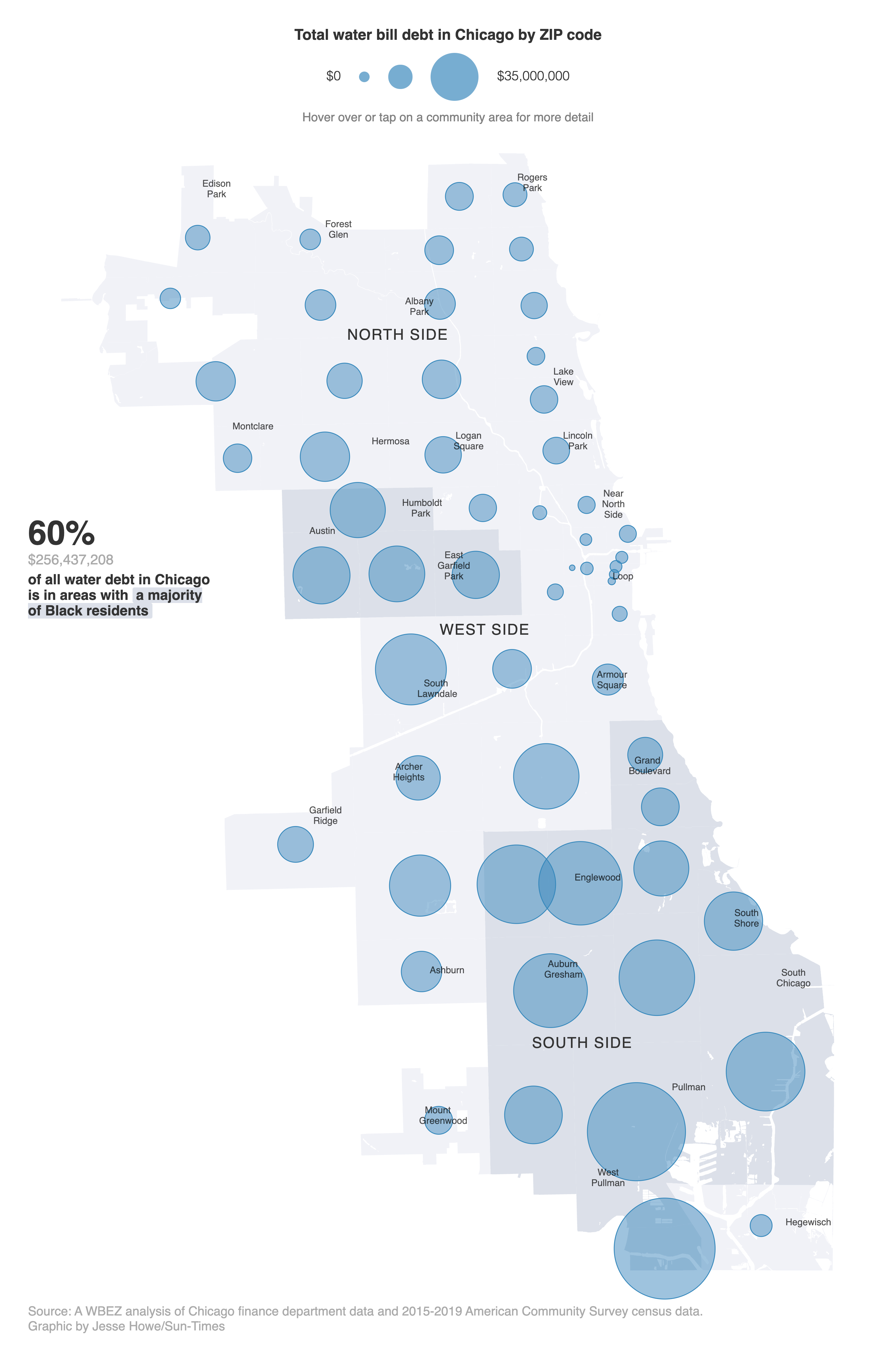

- Chicago homeowners have racked up over $421 million in water debt. More than 60% of the debt is concentrated in the city’s majority-Black ZIP codes.

- The city’s debt collection system has moved delinquent water bills into the hands of private debt collectors, with little transparency. At least $60 million of the city’s water revenue has gone to pay private debt collectors.

- Chicagoans have had millions of dollars in earnings garnished from their paychecks to help settle water debt and many others have faced judgments and statutory liens in an effort to collect water debt.

- An estimated $775 million in water-sewer tax revenue was allocated to the city’s municipal employees’ pension fund, city budgets show.

In a written statement, a spokesman for Mayor Lori Lightfoot touted her administration’s efforts to address water debt.

“Mayor Lightfoot has been focused on improving water affordability for lower-income residents from the beginning of her administration,” wrote César Rodríguez, Lightfoot’s press secretary. “The passing of the historic 2022 budget will provide much-needed funding for disinvested neighborhoods, including funds for water reconnection and additional fines and fees reforms to help individuals get out of debt.”

During the budget hearing process, the city made permanent a pilot program the Lightfoot administration launched last year to help low-income homeowners struggling with water debt. The city has allocated a total of $12 million to forgive the water debt of participants since the program started. The city said 6,300 homeowners successfully completed the program for one year and their debt was forgiven.

But critics say those efforts are not enough, adding that the city should not resort to such aggressive methods to collect payments for a resource that people can’t live without.

“It’s the way cities are trying to collect this [water] debt, but it can end up being very unfair for the customers,” said Coty Montag, senior counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and author of the 2019 report “Water/Color: A Study of Race and the Water Affordability Crisis in America’s Cities.”

Montag said water debt will continue to grow in some parts of the city faster than others.

“When your water rates are unaffordable, and you’re not accounting for low-income customers, there’s going to be a disproportionate impact on Black residents and other residents of color,” Montag said.

Furthermore, some frown on the practice of municipalities taxing water at all.

“Raising general tax revenue through a water and sewer bill is one of the most regressive ways a government can raise revenue,” said Manuel Teodoro, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Chapter 2: How water became unaffordable

Shortly after taking office in 2011, when faced with his first budget deficit, former Mayor Rahm Emanuel increased the sewer fee and added a garbage fee to the city’s water and sewer bills. Within four years, Chicago’s water rates nearly doubled. At that time, Emanuel said the rate hikes were needed to repair the city’s aging water infrastructure.

Those price rate hikes were even higher for homeowners without water meters. In 2013, the city said people in unmetered single-family homes, on average, paid 25% more for water.

But many South Side homeowners, like Carla Padgett, didn’t know their properties were unmetered. Padgett and her teenage son live in a two-flat house she inherited from her grandfather that includes five bedrooms and two bathrooms. She says they use very little water, crediting the military showers her father taught her, but her recent water and sewer bills are about $1,400, on average, every six months.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23005636/WATERDEBT_02.jpg)

Leading up to a divorce in 2015, she started falling behind on her water bills.

In 2017, things got worse.

Emanuel implemented a water-sewer tax that year, specifically, to help pay off the city’s gigantic unfunded employee pension debt, which stood at close to $19 billion.

But Emanuel’s solution to the pension problem fueled a new water debt crisis. Thousands of Chicago homeowners were going into debt because they couldn’t keep up.

Emanuel could not be reached for comment.

After the water-sewer tax was implemented, Padgett’s water bills grew and her debt accumulated at a faster rate than in previous years. In 2017, she was billed about $1,100 every six months. By April 2019, her bill had increased by nearly 30% to $1,415. She continued making payments but not enough to cover the entire bills. Today, she owes the city more than $8,000, with more than $1,700 of it in penalties, billing records show.

“We don’t go on vacations. We don’t do anything extravagant. I don’t buy a lot of clothes,” Padgett said.

Teodoro says working-class Chicagoans, like Padgett, are spending a bigger portion of their paychecks on water and sewer bills. “Water and sewer taxes put a disproportionately heavy burden on the population that is least able to pay.”

An estimated $775 million in water and sewer tax revenue were allocated to the city’s Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund, since the tax was implemented in 2017, according to a WBEZ analysis of city budget documents.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23005666/WATERBILL_11XX21_6.jpg) Tyler LaRiviere/Sun-Times

Tyler LaRiviere/Sun-Times

Naomi Davis coordinated water distribution to those homeowners during the pandemic and tried to help them, and others, deal with delinquent accounts. Those efforts have been difficult, she said.

“We knew that there were programs and funds in place to abate water debt and to avoid shutoff, but this information was not routinely and consistently conveyed by the customer service representatives,” Davis said.

Davis worked together with other local organizations during the pandemic to reconnect water services to Chicagoans and provide free bottled water. As they met homeowners struggling with water shutoffs and high water bills, these organizations started helping homeowners interact with the water department.

“When we would call into the water department, with the authorization of a ratepayer, and we would look to steward the process, or facilitate a solution,” Davis said, “what we found consistently was that there was no consistent quality, there was no consistent information that was being delivered from the customer service representative to the water customers.”

Padgett’s finances worsened during the pandemic. In 2020, when the schools were ordered closed in favor of remote instruction, she temporarily lost her job. Without income, her debt kept growing.

“This is so crazy. … I’m already struggling hard enough just to pay my mortgage, Padgett said. “It doesn’t make any sense. Why would you penalize people for water? I don’t understand.”

Padgett doesn’t make enough to stay current with her water bills. But she makes too much to qualify for the Utility Billing Relief program, which the Lightfoot administration said it created last year to help low-income homeowners. Under the program, homeowners who qualify get a 50% discount on their water and sewer bills and qualify for debt forgiveness. The Community and Economic Development Association of Cook County, Inc., or CEDA, helped the city enroll more than 15,000 households.

On March 1, 2021, Padgett’s delinquent water bill turned into a default judgment for $5,669. That sum includes hundreds of dollars in fees, like a $350 fee to cover the cost of a private attorney who represented the city at an administrative hearing where the judgment was rendered. Padgett missed the hearing because she didn’t get the notice in time.

Chapter 3: Many court cases, little due process

The Department of Administrative Hearings was created more than 20 years ago to expedite code enforcement violations by keeping the violation out of the county circuit court. This administrative court has adjudicated more than 100,000 cases involving delinquent water bills over the last decade.

Administrative law judges issue default judgments when homeowners don’t attend their hearings. Nearly nine out of every 10 cases involving delinquent water debt ended up with default judgments.

Critics question the system’s lack of transparency and due process. However, department officials pushed back. In a statement, the department wrote that “there is a significant amount of due process afforded” and that homeowners have up to 21 days to file a motion to “set aside the default” judgments.

WBEZ interviewed dozens of homeowners who fell behind on their water bills. Of the homeowners who said they had been contacted by a debt collector, none of them knew about the hearings.

The city has outsourced its debt collection to eight private law firms that keep 25% of the water debt they recover on behalf of the city. Since the law firms are paid on contingency, enforcement is aggressive.

Debt collectors have garnished $8.8 million in wages and collected $26.4 million from judgments since 2013. The city also filed statutory liens against 4,500 homeowners between 2010 and 2012. It’s unclear how many of those liens have been released. The city said it stopped issuing statutory liens in 2012.

When asked about ending that practice, the finance department said in a statement that “liens are no longer cost effective.”

Since 2010, Chicagoans have paid more than $937 million to address their delinquent water bills and additional fees associated with that debt. The eight law firms contracted to collect those debts have collectively taken more than a $60 million cut from that total.

Chapter 4: The woman who fought City Hall and won

When Taylor inherited her family’s Englewood home, there was a $478 balance on the account, which was eventually paid off later.

Over the years, Taylor made five requests to disconnect the water, documents show. Just in case she didn’t turn off the water “the right way” the first few times, she said. But she kept getting billed every six months, including $280 in 2007. Taylor paid close to $1,500 between 2008 and 2013 to help keep the debt from growing, she said. But she quickly realized the city would not stop adding new charges. By 2019, she was getting charged $2,200 every six months, almost half of which came from penalties.

Tired and frustrated, Taylor turned to the media for help. She reached out to WBEZ.

“I realized that by myself, I was still spinning my wheels,” she said.

The Department of Water Management declined to answer questions regarding Taylor’s case except to say that the city helped Taylor restore water to her Englewood property during the pandemic. According to the statement, the water department is working with Taylor to verify whether she qualifies for its Lead Service Line Replacement Program, which would also help Taylor get a water meter installed.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23005711/WATERDEBT_05.jpg) Manuel Martinez/WBEZ

Manuel Martinez/WBEZ

In January 2020, WBEZ visited the property, verified that it did not have water and filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the city for Taylor’s account history and other records.

It forced city officials to look through records, and they quickly found the error.

“Her argument and probably WBEZ’s argument is likely that she has been unfairly billed continuously and her property has been vacant since 2007,” an unnamed FOIA officer from the water department wrote in an email to former mayoral spokesperson Hali Levandoski on Jan. 31, 2020, according to internal emails.

“There are some service orders stating the property appears vacant,” the FOIA officer warned about a report that said the entire building was “vacant and water shut-off since 2007.”

Megan Vidis, the water department spokesperson, noted that the report could be an issue.

“Page 14 is an issue,” Vidis wrote to Levandoski and Anjali Julka, former Freedom of Information Act officer for the mayor’s office. “The notetaker was probably parroting what the owner was telling him.”

WBEZ pressed the city to produce the records in February 2020, and that same month the city forgave $21,400 in water debt for Taylor, billing records show. But the fight was far from over. There was still the statutory lien the city had filed against her property back in 2009 in pursuit of $1,100 that the city claimed she owed at that time.

“My mother and father saved to buy this building,” she said. “It would have been a travesty to me for them to go through what they went through to be homeowners and, while it’s in my care, the city takes it for these falsified billings and liens.”

Over the summer, as WBEZ investigated statutory liens imposed to collect water debt, the city sent Taylor a notice she didn’t recognize. The statutory lien against her property had been released.

Internal emails show officials discussing WBEZ’s requests. But most of the emails are redacted, and it’s impossible to know why the city sent Taylor that form.

Despite all the challenges, Taylor said she’s glad the water department finally admitted they were wrong.

Taylor said beating City Hall is even sweeter because the city may have underestimated her — a Black woman from Englewood.

“The water department might say this [is] just another dumb Black person that lives in Englewood, and we don’t have to listen to her ‘cause, you know, she’s stupid anyway,’” Taylor said. “I get that, because that’s what a lot of institutions do.”

María Inés Zamudio is a reporter for WBEZ’s Race, Class and Communities desk. Follow her @mizamudio, and read her past coverage on water shutoffs.

Alden Loury is the senior editor of WBEZ’s Race, Class and Communities desk. Follow him @AldenLoury.

Matt Kiefer is WBEZ’s data editor. Follow him @matt_kiefer.

Mary Hall is a digital producer at WBEZ. Follow her @hall_marye.

Manuel Martinez is a visual journalist at WBEZ. Follow him @DenverManuel.

Katherine Nagasawa was previously WBEZ’s audience engagement producer. Follow her @Kat_Nagasawa.

Charmaine Runes is WBEZ’s data/visuals reporter. Follow her @maerunes.

Tyler LaRiviere is a visual journalist at the Chicago Sun-Times. Follow him @TylerLaRiviere.

Jesse Howe is a data visualization developer at the Sun-Times. Follow him @CraytonHowe.

from Chicago Sun-Times - All https://ift.tt/3wEQWWa

No comments:

Post a Comment